The story follows William Thornhill (Nathaniel Dean) and his family as they recover from their forced deportation from the slums of London to their subsequent colonisation of the land around the Hawksbury River in the early 1800s. The cultural encounter between the Dharug people and the settlers within the show explores not only the well-known brutality of Britain’s imperial violence but also a lighter, more human touch. This is an interaction that is filled with both blood and (some) kindness. Exploring the role of poverty in the motives of settlers of the sub-continent, The Secret River contrasts the desperation of these groups to make something of themselves in a land far away from the class systems back home with the hope of Aboriginal people for them to leave their ancestral lands alone. The important use of the Dharug language means that the audience are put very much in the place of the settlers, which, considering the trajectory of the tour, speaks volumes about the inherited legacy of colonialism.

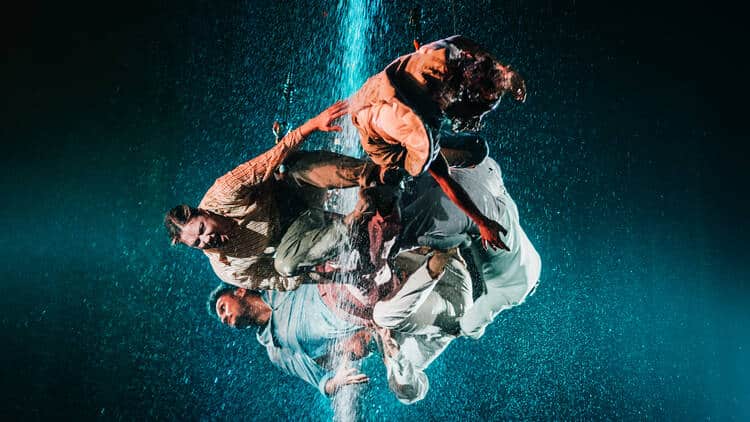

Stephen Curtis’s set, comprising of a soaring tree (utilising all of the Olivier’s height) has a bareness that transports us to the Australia outback with all its rust and dust. Musically, the piece is a triumph, as the Dharug songs, chants and traditional dances provide the real focus and emotional clout of the show, standing tall as a celebration of the ancient culture. Pauline Whyman, taking over the narrator (Dhirrumbin) role, holds the piece together admirably. Georgia Adamson, playing Sal Thornhill (William’s wife), who is constantly pining for London, provides the moments of light and humanity that deepen the narrative. A real moment of contrast from the violence and the thwarted possibility of harmony is when the children of both groups begin an uplifting friendship. This depiction of kindness makes the following carnage all the more painful.

Dean, playing William Thornhill, although providing the fire and contradiction of the — at first — “kind” settler, has a way to go when it comes to accents and the constant changes his accent undergoes is distracting in such a pivotal role. Following up from that, although the set is beautiful and, in terms of colour, perfect, it does feel rather too big for the production and can swallow the actors in the sections of stillness or intimacy.

These are only slight criticisms, however, as the piece is outstanding in its attempt at reconciliation through exploration and open discussion of the past. The use of Aboriginal languages and the mirror held up to UK audiences and our troubling and contradictory relationship to our colonial past, along with the passion of Lawford-Wolf and all of the cast comes together wonderfully. Together they champion the idea that, by understanding the horrors and miscommunications of the past, we can make sure these acts are never repeated. The Secret River celebrates, commiserates and uplifts the story of the First Nations people and that is a real gift.

The Secret River is playing the National Theatre until 7 September