Barbican Centre

‘A Shakespeare classic reborn’

A kerfuffle involving ships in the night (almost literally) is the catalyst for possibly the most famous tale of mistaken identity. Farce is given a pleasantly intellectual facelift by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Phillip Breen’s erudite production.

Max Jones’ set welcomes us into a world of mid-80’s Middle Eastern luxury. An elegantly crafted recontextualization of the city-state of Ephesus looking like Dubai or Abu Dhabi. Characters are draped in Gucci-esque prints, dripping in finery, in a world of lush restaurants, yet presided by despotic Gaddafi-like generals in pale blue uniforms.

The tale is an oldie and a goodie. Two sets of identical twins split by a storm (that never happens) who reunite to unwittingly wreak havoc on each other’s lives. Like The Parent Trap just with less Lindsay Lohan, if serendipity was a play this would be it, with all the creepy twin on twin action you could want (don’t be dirty).

Sometimes dismissed as Shakespeare’s less formed early “joke” work, in the deft hands of Breen the piece tries something new. Amidst this world of opulence and despotic power, shoulder pads, and “gilly” hair, the classic is reborn. The pace is kept high by a musical group looking like The Bangles. Mixing middle eastern wailing, complex choral work with bouncing beatboxing they burst forth to entertain throughout the slick scene changes.

Starting with the Syracuse set of twins, Jonathan Broadbent playing Dromo is an expert comedic genius, making us laugh guiltily in a long section of very fat-ist jokes (interesting you can’t cancel Shakespeare).

Guy Lewis as his master Antipholus captures a blustering brit abroad very well, thrown into the wonderful chaos of the play.

On their mirror opposite, we have Rowan Polonski as Antipholus of Ephesus (don’t get confused, remember the plot, four twins, two cities, and a world of heartbreak). His descent into madness is one of the funniest and yet most painful moments of the play, pointing to the dark reality behind the play’s chagrin smile.

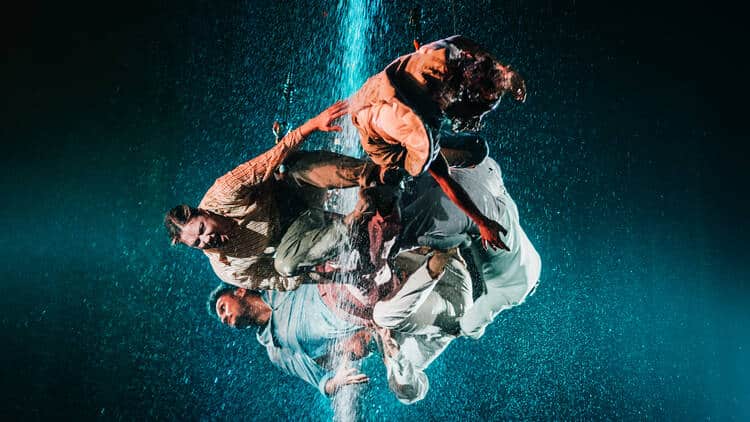

‘A thin layer of comedy over a gram cracker of cruelty’. Photograph: Pete Le May / RSC

Greg Haiste as his own Dromio is amusing but pales in comparison to Boardbent’s frantic energy. Naomi Sheldon, as the unhappy wife of (Ephesus) Antipholus, rules the roost. Hair closer to god, she is sporting a domed (fake) pregnant tummy. This comes from Hedydd Dylan’s (the original Stratford-upon-Avon Adrianna) very real pregnancy that was worked into the fabric of the show. The fact that this production takes this in its stride, and spins it into something interesting is fantastic.

Adrianna’s mood swings and sense of urgency at her husband’s philandering make perfect sense and Sheldon’s fiery and hilarious outburst makes her unmissable. Not alone is the sense of trying something different, and not alone does it pay back tenfold.

William Grint as a terrifying merchant and his bodyguard/translator Dyfrig Morris make a side-splitting pair, as they speak in sign language. Proving once again that talent knows no limit, what a hotbed of comedy and diversity.

We get effeminate guards, masculine nuns, and assertive servants all adding to the melting pot of misdirection and missed connections.

Most actors clearly understand the brief, a thin layer of comedy over a gram cracker of cruelty. Toyin Ayedun-Alase as a jumpsuited Grace Jones-esque courtesan, Baker Mukasa, as the conniving gold merchant Angelo, Alfred Clay as a yogi, spiritualist Doctor Pinch, all thrown in the path of the luckless twins. They demand to be seen, pulling every comic drop out of the script, leaving us in puddles of giggles.

Admittedly the premise could wear thin, as the double doppelgangers rush on and off stage, charged with the crimes of their previously exited long-lost siblings. But quite the reverse is true, the second act descends into delicious chaos, heightening the circus-like snowballing of accusations.

Both sets of twins sustain a manic carouseling of action, but everyone involved understands the sense of fatalism that hides under the jester’s cap. The fragility of human relationships, that madness or meaningless that lurks just beneath. Throw your head back and chuckle at the antics on stage, but are you so far from losing it all? Are we complicit or just spectators in this particularly wonderful Comedy of Errors? Unlike a lot of Shakespeare’s comedies, is there a happy ever after when the dust settles?