Stone Nest

A high energy interpretation of a deeply personal history, this story is warped by intimate contact and left me, as a spectator on the outside, confused.

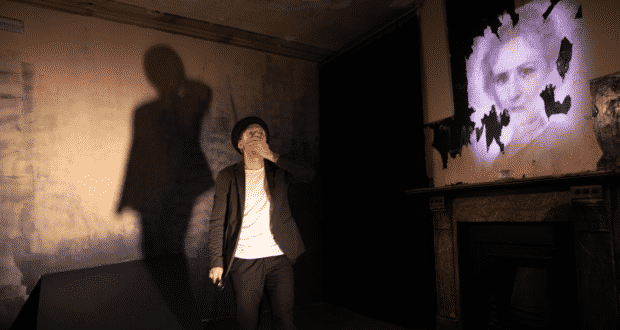

Nestled in the charmingly distressed upstairs room in the beaten and battered Stone Nest (formerly the Welsh Curch) and overlooking Shaftesbury Avenue, the piece is site-specific, although the only interaction constitutes opening a window. Undeniably there is a good tune to this particular jig. One-man shows are a tough song to sing, and throughout Bennett’s energy is high, along with his believability.

Yet the spectre of writing raises its monstrous head to ruin the party. The piece is overly descriptive, requiring Bennett to constantly explain what he is doing instead of acting it: “I woke up in a hospital, I talk to my cousin on the phone, I eat a sandwich”. The constant reference to self takes away the magic of seeing a good actor inhabit an imaginary space.

The story begins to mystify, as we jump between Bennett playing himself, an out-of-work actor during the recent pandemic trying to find his grandfather, and him playing his father; or grandfather? or great-grandfather? It’s rather hard to follow, although the contrast of his RP accent and cockney is clear as day.

There are moments of charm, snatches of songs and bright spots of comedy. Being a pay-what-you-feel show, it’s an idea that the ghost of Henry Hollis would appreciate. Vladimir Shcherban’s directing has many moments that are well thought-out but become repetitive during the hour running time. The use of projection is simplistic, with varying success. An emotional section during his grandfather’s time in the navy during WW2 shows raging waves consuming the corner of the room. The flaking paint adds a divine fragmentary feel to the many old photographs used throughout, the first time. But this interaction with flat surfaces and images is used so heavily that we no longer enjoy it. Again the use of puppets is a staple for lonely one-handers, but Irina Gluzman’s terrifying figures only manage to add a rather menacing visual language.

It is a brave thing to put your family history out into the world, but you also have to make sure it is understandable for people who don’t share your genetic blueprint. The world of 1960s London feels surprisingly far away considering our location, and without many songs or musical instruments (apart from the impressive skill of playing the spoons), the metaphorical hat passed around looks mournfully empty.