‘Writing at its most perceptive’

Lolita Chakrabarti’s (prestigious writer with the best name in existence) new piece is concerned with two sadly underrepresented topics: men’s mental health and black masculinity.

The bite-sized production, live-streamed from the Almeida Theatre, comes out sprinting, even if by the end it stumbles slightly over its own feet.

We are pretty used to digital theatre by now, right? I’ll skip the obligatory joke about the difference in experience, and the mention of my pyjama-wearing, unwashed body, and crack on with the show. We are all bemused children of the apocalypse now.

The screen fades from black to the familiar stage (sans seating) with a strip of wood panel spreading down from the ceiling in a triangle. A piano and a metronome sits at the back and straight away Prema Mehta’s lights cast a cinematic and amplifying tone.

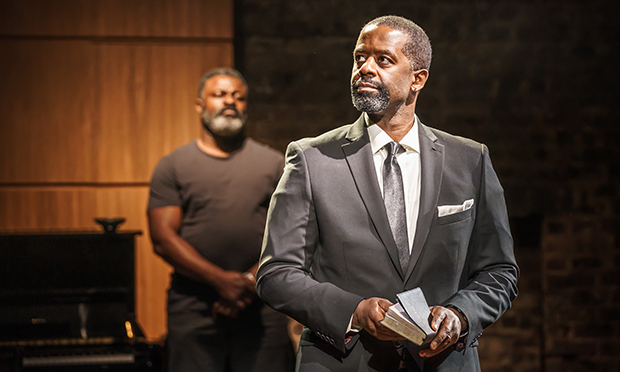

This two-hander allows Adrian Lester and Danny Sapani to showcase their style and versatility. Following a meeting at a funeral, these two men, linked by one thing but divided by everything else – upbringing, class, confidence – start to rely on each other.

The roots of Hymn are deep and tap into so many interesting reservoirs. The pair speak about navigating the world as black men, the struggles of their upbringings and bringing up children, family pressure, and personal/business success (to name a few). Chakrabarti’s focus on the intersectionality of race, gender, and class is writing at its most perceptive.

Visually, Blanche McIntyre’s direction pulls out a magician’s repertoire of tricks to keep the monologues and dialogues from being weighed down by the loquacious script. The rich singing voices of the actors and the piano playing of Lester are a welcome diversion from the constant emotional mangling.

The piece is slick with block-colour lighting and expert camera work. The zenith is a monologue in a church when, with only a strip of LEDs, a good spot and a close-up, we are transported into the hushed sanctum of a funeral. There are also a few dance sections that, although fitting to the plot, run on a little long.

As Sapani’s character Benny is welcomed into a new family, the bond of friendship and mutual improvement builds to a sadly rather predictable fall. This is where the production – at first so energetic and ripe – starts eating its own tail. Time seems wasted on less important moments and then the crucial last section of reckoning and hubris feels rushed. The confrontation between the two men and Lester’s character’s destruction feel over in the blink of an eye. It’s like filling up on bread and then being unable to finish your expensive steak.

Lastly, although the actors manage wonderfully and a large cast is impossible at the moment, you do find yourself pining for the strong female characters that are mentioned throughout the piece. Maybe some use of projection or video calls might have varied the pace and lessened the pressure for the two blokes?

Despite a rather bungled ending, everything pulls together for a strong piece of theatre which showcases the considerable strength of Lester and Sapani’s talent and rams home the crucial difference between live and prerecorded acting.

The reality and fragility of humanity, along with the importance of open communication, are heartbreakingly felt throughout. Can watching repeats of Gilmore Girls on Netflix do that? Excuse me while I sob down the phone to my mother – completely unrelated of course.