Almeida

Beth Steel’s kitchen sink drama weaves the incongruities of family and the reality of our two-party system into the dreams of the Websters. Heavy going, dense, and delightful in a particularly dreary blood-stained sort of way. Right up my jitty (alleyway for the southerners amongst you)!

Having grown up partly in Sheffield the reverberations of Thatcherism, the loss of the industry, and New Labour have always been very present for me. The southern stick of “grim up north” always felt barbed, not bothering to mention the very reason for this deprivation. Many cities, Sheffield included have reframed themselves into cosmopolitan centers rivalling their southern counterparts but the wounds run deep.

In the middle-class heartland of Islington, these slashes both political and personal (is there any differences?) are unravelled in Steel’s mammoth dynastic drama. 1965, 1979, 1985, 1996 and 2019 (all politically divisive years) roll by almost seamlessly as the face of Nottingham, and the people who live there change irreversibly.

Anne-Marie Duff is our centre; Constance, with a heavy slosh of Bette Davis as Margo Channing in All About Eve. This is all the more perfect because Constance quotes her favourite starlet (Davis) throughout the play. Duff’s performance is spiteful, painful, and woeful. Her preoccupation with the at times unwanted job of motherhood is refreshingly thrown against the political of fervor of her family. As the years roll by we see the spark of hope fade in her eyes, and the glamour she so longs for fall from her shoulders. A performance of a lifetime indeed, deeply impressive due to its paper-thin layers. Duff is playing Constance, who in turn is trying her best to affect the classic Bette Davis eyes in her utterly glamourless world. Dolls in dolls in dolls.

Churning the family dynamic she faces off against her husband Alistair, played by Stuart McQuarrie. As a mouthpiece for the peaks and troughs of the Labour and union movement the character’s density of speech is humanised by Mcquarrie. Their twins Agnes (Kelly Gouch) and Jack (Michael Grady-hall) clash in a way that highlights the 80s at their most polarising. One feeling the devastation of Thatcher’s battle with the miners, the other riding high on the island of small businesses. Both provide eruptive performances, but Gouch especially shows a graceful and tactile depiction of a woman supporting her family.

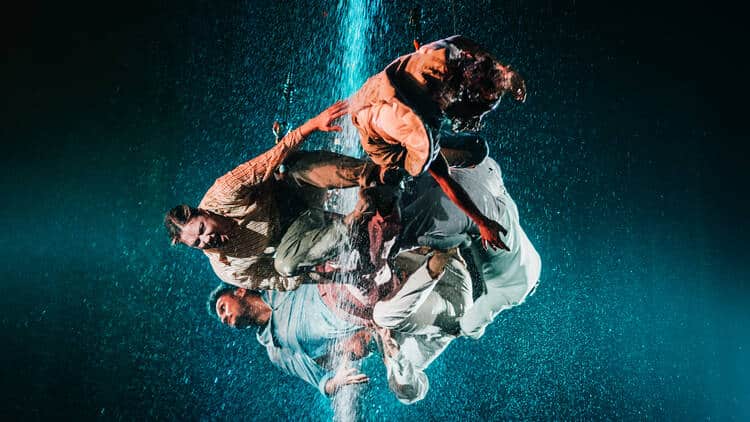

Anna Fleischle’s set is flexibly naturalistic, the living room dissolving as the times change. Liam Bunster’s costumes keep us grounded as time races along and Richard Howell’s white flashes (like snapshots) serve as helpful bookends to each scene.

Covering 54 years is a tall task. Blanche McIntyre’s directing is psychologically realistic, focusing on the emotion of the characters, and allowing the didactic message to flow from that. However, the maybe practical, maybe artistic move to have muti-rolling actors play their characters own children, or parents then play their elderly child is as confusing as it sounds. No matter how effective the actor’s ability we find it hard to split the face from the character. Especially when they are speaking regularly about the character they have just been playing. Carol MacReady although delicate as the elderly grandmother Edith disappoints as the elder Constance, the only person who seems to find the distinctive accent difficult. Lastly the first act is a little long at 1 hour 30, I heartly agree with a fellow audience member’s lamentation that “everything is too long nowadays”.

That aside this play is utterly relentless. Death is a constant presence, along with poverty, misery, hatred, and resentment. Reappearing ghosts crowd the space, giving a rather bleak view of not only northern but human relationships. The last line “we’re family” is spat out as an almost inescapable curse, implying that we can never escape the political reality of our life or the social reality of our upbringing. Mirrored by the characters in the play, as shown in the egging of the most recent iron lady, or the 14% rise of child poverty since 1979 the scars of the country’s past are far from healing.

If you want to see what outstanding theatre is on next, click here!