National Theatre Live on YouTube

‘Hamilton’s less musical British cousin’

Alan Bennett’s royal romp, performed at the Nottingham Playhouse, quickly deep-dives into the tortured mind of 18th-century ruler King George III.

There may be ruffles and tights aplenty but this is far from your classic period affair.

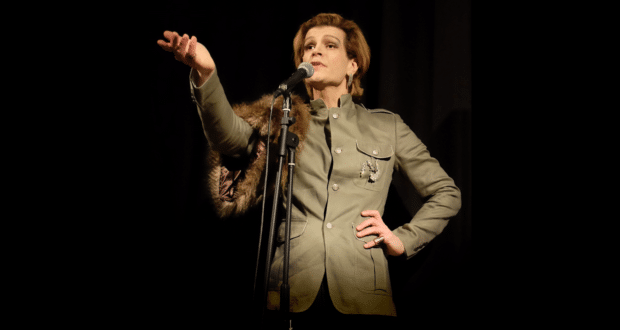

Following in the footsteps of Nigel Hawthorne and David Haig, the title role is a big crown to fill for Mark Gatiss. As a well versed comic actor, along with being a king (puns ahoy) of the dry one-liner, he brings an amazing vitality to the role.

The descent into madness is meticulous, uncomfortable and, in the second act, heartbreaking, but it is still peppered with lighter moments.

Gatiss makes the role his own, which is always helpful when one plays the eponymous character.

Adam Penford’s direction is swift and focused, pulling the best out of both Bennett’s writing and the prodigious talent of Gatiss.

An interesting element of the piece is the cruelty and corruption surrounding the King’s mental state, from diabolic doctors to the truly dysfunctional royal family.

The history of medicine is a major feature, along with the view of the American war for independence, making this a bit like Hamilton‘s less musical, very British cousin.

Bennett’s writing is imaginative, touching on politics but still making the characters’ feel personal, and bringing a fresh perspective to long-dead events.

Robert Jones’s set is a Baroque Rubik’s cube, unfolding fabulously from one gilt palace interior to another, a physical ballet of state. Maybe I watch too much theatre but is there anything sexier than a set-piece floating down from the ceiling and landing without a sound? No, no there is not.

Tom Gibbons’ choice of an appropriate, harpsichord-heavy score that grows more and more discordant as the King mentally disintegrates is a subtle way of building tension.

Some wonderful gender-bending sees Amanda Hadingue playing Charles James Fox and Nicholas Bishop playing William Pitt face off as political nemeses, giving a flash of a political system so far removed but still scarily familiar.

Debra Gillett plays queen Charlotte with the needed regal gait and bright sections of quiet humour.

The second half is stripped of much of the lightness and is a troubling depiction of the state of mental health care in the past, and the complexity of treating a king.

Adrian Scarborough as the best-of-a-bad-bunch Dr Willis provides the closest to kindness we see outside of the queen, stating: “Who could say what is normal in a king?”

Bennett does throw us some bones of hope here and there and a section where the king recites from Shakespeare’s King Lear is as poignant as you would imagine.

As the vultures swoop over the man reduced from royalty to victim, Bennett and Gatiss shine, pulling away the stiff layer of court life to show a man fighting his demons in an inhuman and unique position.

This piece is surprisingly affecting for a historical work, as the amount of power held in such very human hands points to flaws in the divine right of kings.

What can we do when those in power wield it badly? It’s a question that still plagues us today, though in a slightly different uniform.