Like with chocolate, cocktails or puppies, two for the price of one is a wonderful concept. When both are free it loses none of its magic.

Thus the Wilding clan settles down for two nights of the haunting 2011 production of Frankenstein, which saw Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller switch between the roles of monster and creator on alternate days during its run.

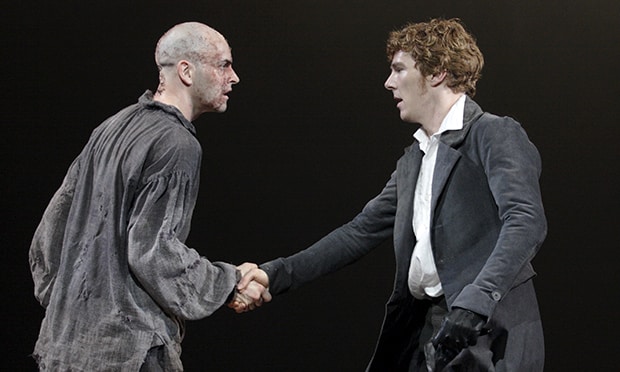

Dealing with the quirk of the production first, I experienced Cumberbatch’s monster and Lee Miller’s Victor and then the reverse.

Perhaps any comparison is unfair when the latter show is fresher in the mind, but it’s only in comparison to Cumberbatch that Lee Miller’s monster falters.

On its own, his performance is a detailed and spirited look at the physical and emotional turmoil of a man created. But it just doesn’t have the otherworldliness that Cumberbatch brings to the role, with his frighteningly childlike spasms.

Cumberbatch is utterly transformed. He avoids not only the trappings of accepted human speech and movement but any monster-like caricatures when he becomes the newborn, highly conflicted and loveless creature.

Other cast members, such as Karl Johnson playing kind teacher De Lacy or Naomie Harris as Victor’s betrothed, stand out, but it is the two sides of Cumberbatch and Lee Miller that dominate the show.

Their role-switching somehow underlines the connection between the man and monster.

The play, based on Mary Shelley’s brooding novel, races along at a clip, and although terrifying, loses some of its depth in Nick Dear’s rewrite.

Victor Frankenstein selfishly creates a monster, who then begins to question his place in the world. The themes of atonement, along with existential doubt, are kept.

But large sections of the book are passed over, including the whole character of Captain Robert Walton and his ship.

Dear’s decision to do away with this framing section, although it speeds up the piece, creates a much simpler, linear structure, with less of the intricacy and unpredictability so loved in the novel.

Visually, however, the piece is flawless. Hundreds of pulsating bulbs hang in a spray pattern from the roof, a reflective ceiling of silver, like the often mentioned firmament of the heavens.

The set is predominately bare with sections rising up or being pulled on from the gloom at the back.

The Olivier’s famous Lazy Susan, turntable stage lifts a charmingly gothic drawing room, which interestingly is on a slant – a lovely detail.

Mark Tidesley’s steampunk aesthetic allows for magical moments – whole trains race on stage, suspended bells chime, fire leaps from the floor and wombs of skin pulse.

When combined with Bruno Poet’s lights, which conjure the smoky Alps of Switzerland and the freezing plains of the North Pole, the result is a heady mix.

Suttirat Anne Larlarb’s costumes, and the incredible make-up work on the monster, give an elegant (in a grotesque sense) interpretation of its hodgepodge body.

Despite the brisk speed of the tale, the sense of dread, fear and cruelty encapsulated within the novel is expressed by both actors in their embodiments of creature and master.

Danny Boyle’s vision is a stripped-back one, concerned with the philosophy and emotion at the heart of the story.

The fantastical nature of the tale is brought into a more realistic and painful realm as the audience is forced to watch the treatment of an innocent and abused individual.

As the book did with contemporary readers, the play forces a mirror up to our supposedly civilised world, and what stares back is monstrous indeed.