Battersea Arts Centre

Change is something all couples go through to some degree, nay all humans. Typing this as someone in their 9th year of relentless relationship tectonics I can confirm. But do many of us want to open up one of the most fundamental changes a person can go through to the paying public?

Rosana Cade and Ivor MacAskill very much do, and we are very grateful for their bravery and utter silliness. Meeting as two lesbians and subsequently dating, MacAskill’s gender journey resulted in them transitioning to a man, during this process Cade also discovered that they were non-binary. Instead of tackling this turmoil in private with wine or counselling they decided to make a two-hander, queer retelling of the Italian fairy tale Pinocchio, as you do.

These two are theatre veterans based in Glasgow with various hits throughout the years. They bring this artistic, cabaret, punk, experimental know-how to the task in hand, a tale that is as marvellous as it is totally mad.

So everyone’s favourite talking kindling, proclaiming to the world that he is a real boy, beset by doubters, giant whales and a whole island of pleasure. Tack onto that a propensity for speaking his truth, leave out the whale part and what do you have? A perfect analogy for the transformative journey made by Cade and MacAskill.

But can two people craft an effective fairy tale, complete with nods to the famous 1940 Disney film? Well, you position it like a run-through, filming the process of the making of the play within itself. Got it?

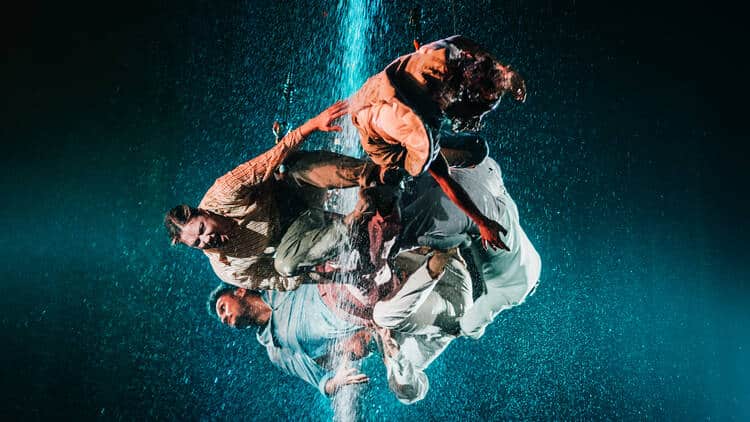

It’s all about perspective. Philosophically the perspective you gain from following your own truthful path, but also a very practical perspective. Let me explain. We are greeted by the chasm of the BAC main space, with the vaulting ceiling of the 1900 grand hall darting above. A sheet creates a wall running up stage right, that also descends to cover the floor stretching to stage left. Odd what look like modernist statues that turn out to be puppets, with wigs and props lined up on each side of the “stage” that is tilted away from us. A large screen is hovering over all this facing the audience. Filming into the sideways stage, they project the image onto the screen. We are seeing the side of the action along with the front-on end result. The double frame of reference creates a brilliant deconstruction of how the piece is being made and how the perspective-based tricks are being accomplished. We are both audience members and cast members watching from the wings, simultaneously. A theatrical chef’s kiss indeed.

The whole team must be commended, not just our in-love stars. Jo Hellier as performer and sometimes cameraperson/cinematographer. Tim Spooner’s minimalist but clear costumes and set (and also sometimes performers and cameraperson). Kirstin McMahon’s cinematography and Jo Palmer’s high contrast lights and lots of bright noggin work gives us some disarmingly simple old fashion movie stunts. The duo float in the sea thanks to wooden sticks hung closer to the camera, converse with fairies (a talking spinning glittery box) and clamber over each others gigantic bodies. Who knows where the fourth wall is at this point? Or are we in the 5th and 6th dimension here? It is the opposite of being asked to suspend your disbelief, a cynical and risky bit of theatre work that completely pays off. Keeping us avidly switching between polished screen work and in-progress reality.

Couple this ongoing inventiveness with a truly madcap script and you get an evening of frantic energy. One thing I doubt I will ever see again is MacAskill on stage fully naked, singing a duet with a video of their pre-transition self, also nude. When You Wish Upon a Star warbles on with past and present MacAskill singing in different keys, and body shapes due to the hormones and surgery. Once in a lifetime, spellbindingly beautiful, and dreamlike. This frankness from both MacAskill and Cade, sprinkled with rye humour about their relationship allows the 90 minutes to almost fly by (although as I always say it could lose 20). They bicker, snipe, and debate in a way that is familiar to everyone in the room. An ordinary couple going through something extraordinary. The word “darling” never had such myriad meanings.

Children’s theatre cheerfulness and mine does slip in from both (due to past work we assume) but is unsurprising considering the subject matter. They quickly pull it back with filthy interpretations of Pinocchio’s growing nose and a rather harrowing transformation into donkeys (don’t ask). Giant inflatable monsters cause an up-close filmed orgy and the couple also manages to simulate sex with wooden snap-on meccano-like props. A propensity to keep hammering the joke from laughs into the uncomfortable is felt throughout, but at many points, this extension circles the whole affair back to funny again.

Queer theatre has a rather unfair reputation for being self-absorbed, and on paper this show is. But with the discussion around trans rights being brought to a boil, witnessing two humans struggle with the age-old question of identity, and it also be breath snatchingly entertaining is a stratospheric success. I promised I wouldn’t make an on-the-nose joke, and I don’t think I need to. This show asks, why don’t we believe Pinocchio when he says he’s a real boy? And what it means to change, both yourself and in a couple. Questions we would all like answers to, and with The Making of Pinocchio I feel a giant leap closer.

Click here and grab your tickets toot sweet!