Central School’s Format Festival kicks off with work by Advanced Theatre Practise MA students. In the depths of a basement in Camden, we get splattered paint, and bubbling desire. Sign me up and then some!

Me Looking at Her Looking at Me (or MLAHLAM as it will now be named) has brush strokes of fine art and performance art, specks of naturalism, sprays of projection, and a couple of litres of paint. Now having worked as a life/portrait model for years myself this subject is one I know a little about. The relationship between artist and muse. It’s an awkward, and historically problematic one. Mentioned very quickly by MLAHLAM is the famous incident of 19-year-old Elizabeth Siddall. Almost getting hypothermia as the candles warming her bathtub went out in winter while John Everett Millais was so engrossed in his painting Ophelia. Although the days of laudanum-addicted teenagers and sex workers dominating the life model industry are (mainly) over the power play between someone willing to sell or give their image, and an artist consuming it, is as ever a complex one. Something the piece captures pretty realistically.

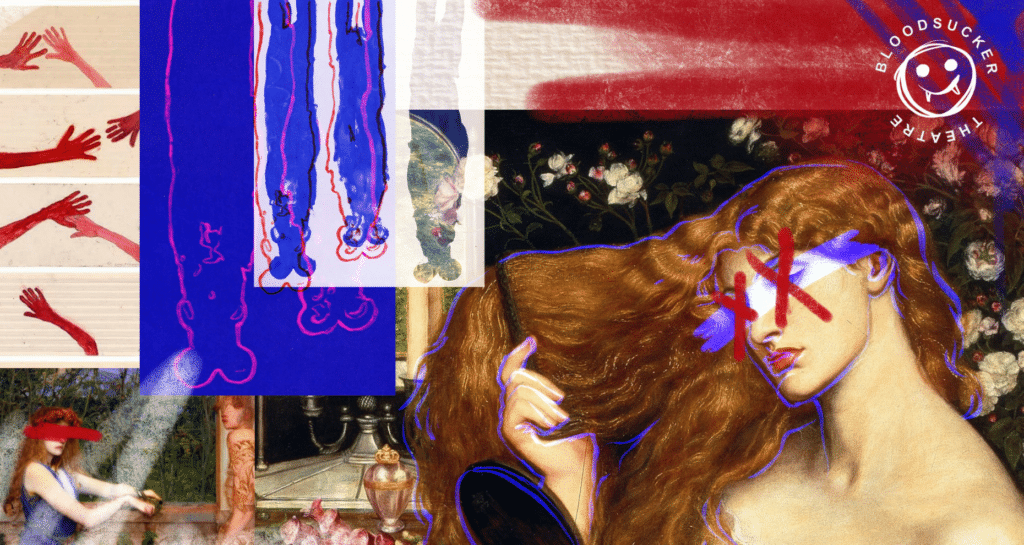

Artist played by Eden Peppercorn, and Model played by Claire Eyestone dance this tango of power. Where this piece shines is its reliance on projection and artistic eye. A simple handheld video camera projects Peppercorn’s intent face as they paint the tumbling tresses of Eyestone. Devian Maside León is in the corner of the white-washed basement manning all the tech and doing a slap-up job. Blue, then red washes craft cinematic intensity as the actors make the stunted small talk of a portrait session, or dive into deep discussions on perception. Eyestone’s pre-Raphaelite curls and overall aesthetic along with various nods to the history of art throughout are nice touchstones. Pomegranates (meaning resurrection and life everlasting in Christian art) are devoured, paint is splattered, questions are written and superimposed on the white sheet, and loud punky tunes are blasted into the claustrophobic space. This tale of friendship, obsession, desire, and possession disintegrates around the heads of our characters with predictably bleak consequences.

Less successful moments come from sections of dead space, where little is happening and not much is conveyed. Long periods of putting up the set/props (15 minutes) which surely could have been done before our entrance rather dilute the proceedings. Despite experimental sequences, the main body of the show is very static as we watch Peppercorn paint and Eyestone snack. The well-written dialogue does distract from the theatrical doldrum but not enough. Again, breakdown moments descend to the floor. But with the lack of raked seating everyone apart from the front row is stuck imagining what the grunts and shuffles from the actors might mean.

Although mutual but forbidden desire is present throughout the long-awaited crescendo is more like a slowly deflating balloon than a bang of action. Late-in-the game shoehorning AI-created art feels rushed. Bright aesthetic eye, and impressive visual technical abilities aside Bloodsucker Theatre needs to focus more on what makes a piece interesting for an audience. But keep the artworld sensitivity that they already have by the bucket load.