Royal Strafford East

30 years ago, in 1993 Jonathan Harvey wrote and performed something beautiful at The Bush Theatre. Now on the anniversary, the hit play turned TV movie, then big screen sensation settles into the grander of Theatre Royal Stratford East before touring the UK. What a long way it has come.

A little extraneous background. As a gay-ling in the late 90s, queer films were thin on the ground, thicker than they had been previously of course but still, slim pickings. Beautiful Thing was one of the first films I saw that featured a gay love story at its heart, with a happy ending. Yes, the South London council estates and strong accents felt a world away from the Sheffield life I was living, but the struggles of Ste and Jamie were a speck of hope in a storm of isolation that I and many others felt growing up.

Does the film feel dated now? Of course, it does (although please still go watch it). Yet it captures a snapshot of life: each character battling their demons, along with those loaded on them by the people around them. Compared to the AIDs crisis, homophobic Thatcherism, and the higher age of consent (21), we have come a very long way since 1996. Although drag bans in the US, transphobia, and the ever-present bullying and suicide remind us that there’s still a long way to go. Enter Beautiful Thing, a gay love story and so much more.

When I saw it was being revived, I almost begged my editor. Anthony Simpson-Pike’s attempts at updating the play are smartly done. Swapping the races of the main characters is a novel way of remaking the story: bringing a whole new set of meanings to the discussion of working-class life in the capital.

Lioness mother Sandra dominated the film, and of course she would, being played by Linda Henry. Shvorne Marks makes the role her own, this ferociously loving, mouthy, and at times physically abusive mother is a tough nut, both as a character and for an actor. Marks well and truly cracks it, snarling in her no-nonsense monologues and snappy bickering with her son Jamie. Equally Trieve Blackwood-Cambridge does well with the comic-relief character of Tony. Sandra’s new-age hippy (secretly posh) boyfriend, making him likable as well as funny.

Scarlett Rayner is the Mama Cass-obsessed neighbour Leah, providing the blasting soundtrack through the paper-thin walls of her flat. Although this role is one of the funniest and intricately laced with sadness, Rayner misses a few opportunities. A little two-dimensional, but more effective in big group scenes, or in her constant back and forth with Sandra. Our leads Raphael Akuwudike as the sporty Ste and Rilwan Abiola Owokoniran as the sensitive Jamie build a gentle connection with one another. The slow progress from friendship to something more is lovingly grown, cramped into Jamie’s minute bed. But slipping accents and some repetitive blockings get in the way of the tender tale. Harvey’s machine gunfire of dialogue, between Sandra and pretty much everybody is present, still riotous but feels hemmed in by the set, paced at rather sporadic speeds throughout.

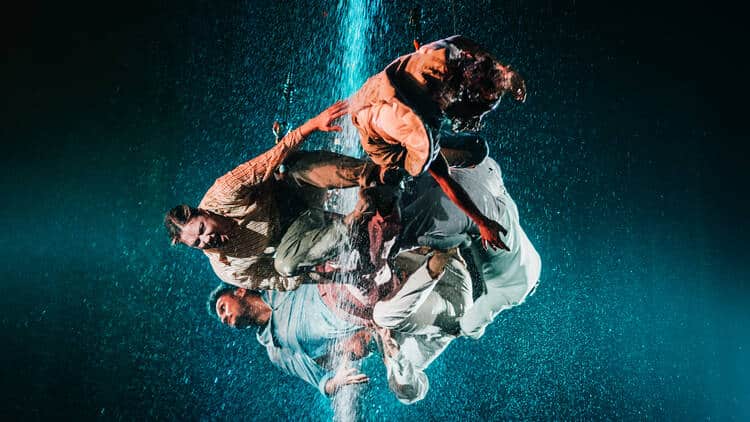

Rosie Elnile’s vision of the estate is a wall of that textured concrete favoured by brutalism, 3 doors, the patios out front, and nothing else. We never get the interior of the flats properly, with only a small bed pushing out from the wall and a focused spot to indicate we are inside. It’s unchanging, inflexible, cramping the characters, limiting blocking in a large space. Eventually, it opens out for a final reveal that is underwhelming at best. A major theme is the proximity these flats create and the sense of community. I understand the choice to only show the public lives, but the chance to compare private and public is sorely missed, making the scenes drag on with little visual interruption.

In fairness, the film might be pumping in my head a touch loud, as more of the storylines are fleshed out. Ste’s problems with his abusive father and brother are a difficult but welcome edition in the big screen version but frustratingly mentioned only offstage in the stage. Also, the character of Leah is given a bit more spotlight to counterbalance the romance, improving the tale greatly.

With Heartstopper, Love Simon, and LGBTQ+ films released regularly people growing up won’t have the same excitement as I did over Beautiful Thing, and that itself is a beautiful thing (sorry painful pun). Yet it still has a lot to say about the state of the nation in the 90s and the ongoing struggles for acceptance. This recent revival applies a new lens from which to understand Harvey’s enduring piece, even if the set it’s encased in does its best to flatten it.