Matthew Bourne, Sadlers Wells

After 9 years of absence from the London theatre scene, Matthew Bourne’s balletic version of Caroline Thompson, Tim Burton, and Danny Elfman’s 1990 classic film returns with blades a-swishing.

Thompson’s screenplay is a riff on the Frankenstein myth, Kookified by Burton and bolstered by Elfman’s expansive musical vistas. Edward, for rather vague reasons, is made with knives for hands by a mad scientist, then abandoned after his creator’s death. “Welcomed” into a Wisteria Lane/Whoville-esq 50’s suburb by the kind housewife Peg, he struggles to connect both physically and psychologically with the squeaky-clean American dream. The clumsy metaphor of his inability to touch hints at the plot not being the main reason for the movie’s success. But with much of Burton’s career, it’s his gothic/Halloween aesthetic and Elfman’s over-the-top score that kept the audiences coming back for more.

So, what can the bright hope of ballet’s future (Bourne) do with such a tale? On paper, it’s an easy slice (ha ha he he). It has the clear visual palette that leads itself to larger-than-life sets, and although a man with knives for hands would make a delicate lover, he certainly makes a wonderful central dancing figure. Bourne’s comedic and sensualise approach to the (sometimes) serious world of big-budget ballet should vault in a tale such as this, of outsiders, hidden truths, and the struggle with conformity.

But this ballet strikes the same wall that many make-them-dance versions of famous films or books do—the silence of the performers. Ballet is a quiet art for almost all involved. Yes, we still have Elfman’s sublime music and the New Adventures Orchestra who bring it vividly to life. But without any speaking from those involved on stage the plot mists, and the whole affair at its worst points feels like a very expensive game of charades. Beautiful but stony quiet athletic bodies trying to “dance-act” complex conversation, with very little success.

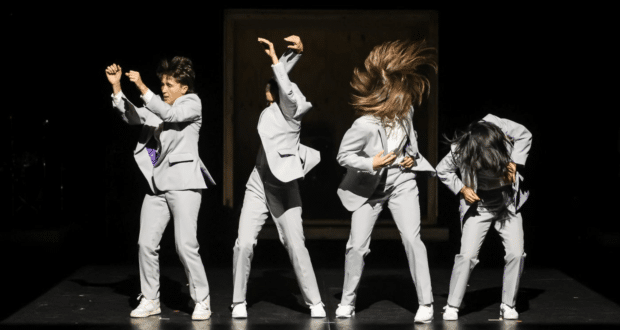

That doesn’t mean that visually there is nothing desperately trying to charm your eyes. Lez Brotherston’s costumes are true to the film’s overexposed palette, and the set likewise are gigantic interpretations of the already theatrical Burton originals. There are moments where Bourne’s choreography crafts something just glimpsed in the film, but they are few and far between. An animated hedges section where the corps de ballet don leaves and blooms into a topiary tango brilliantly showcases dance’s ability to be more experimental and dreamlike than film. Liam Mower as Eddy-pointy-digits does his best impression of Johnny Depp’s pursed lips and social awkwardness. However, when you add on all the leaping and spinning balletic requirements he ends up with an indefatigable standalone lead.

The edition of a gay couple added to the Stepford knockoff is a pleasant update. Edwin Ray and James Lovell provide many chuckles as the comically waspish Modern Family-style middle-class homosexuals.

The production is not short on comedy, and this lightness is a hallmark of Bourne’s success within the occasionally sour-faced dance world. However, as a massive fan of the film I found myself clenching my fists, muttering under my breath “Just speak dam you” as another “conversation” arabesque and pas de chat’s its way across the stage. This production merely replicates the positives of the original, not bringing much new to the table, and losing some things in the kicking limbs. Despite all the flashing blades, its tendency to over-literalness dulls anything remotely resembling an edge.